On Japan

Japan, like any country, has a complex and nuanced culture that contradicts itself as much as it coheres. It's layered and flows, only exposing itself in fits and bursts to someone like me, a visitor, a layman, a gaijin. I certainly wouldn't claim to be an expert on the things I attempt to talk about, but these are my experiences and thoughts. Let's start with a story.

Almost all of my interactions in Japan were at least cordial and the majority were displays of vast humility and hospitality that I've never seen anywhere else I've traveled to. One particular old man, however, gave me a glimpse into a side of Japan that I had heard about but had never experienced. While looking for a place to eat with Wendy after a day of temple and deer viewing in Nara Park, I suddenly hear someone shout, in English, that I should go back where I came from. Confused at first I start laughing, unsure of the direction of the insult, but the old man quickly repeated himself and made it clear that he was talking to me. There was mention of my unwelcomeness, of my being unwelcome because I was taking their Asian women, that I should go home and get a woman from there. Expletives were introduced. His English was actually better than most people we had met. I mention that Wendy isn't Japanese but the man seems unfazed. We leave with mixed emotions and sit down to eat, still trying to process the encounter, when another old Japanese man sits down and immediately notices us. His face and voice give away his inebriated state, but he's all smiles and praises for American baseball and Hollywood movies, quoting his favorite films, telling me how much he likes the New York Yankees and Derek Jeter. His English isn't as good as the other old man, and he mixes in pieces of Italian and French, but his joviality couldn't be more clear. He laughs at all of his own jokes and offers me some sake, telling me the deer in Nara are protected and so I shouldn't shoot Bambi. He talks to us the entire time we're there until we go to leave, me thanking him for his generosity and the smile on his face having never left. The abrupt shift from one end of the spectrum to the other left me dazed, my head still spinning from two interactions that couldn't have been more different in the span of less than five minutes.

Japan has meant different things to me through my life. Growing up on video games and animated ninjas put a vision of a futuristic utopia based on an ancient noble heritage in my head, a notion that lasted long enough to take me there with two friends in 2006. In some ways the vision held up. Tokyo's train system is a marvel, expansive enough to get you anywhere in the city, accessible without knowing any Japanese. This is true for most of Japan, that you can travel the entire country by train, though English does tend to disappear outside of the major cities. I was also astounded by how polite almost every single person in the service industry was and how quick they were to go above and beyond to help an obviously clueless visitor.

In Yamanouchi, on our way to visit the Jigokundani Monkey Park to see the Japanese Macaque bath in the hot springs, we exit the only local station and immediately notice the lack of English anywhere. Without knowing what else to do, I pick a street at random and begin walking, hoping to find someone to try and mime directions with. I walk into a hotel, fancier than the pictures told me to expect from my booking, and ask the the lady behind the counter if she knows the direction of the address in my hand. Instead of pointing a finger or drawing a map on a notepad she walks out from behind the counter, out of the hotel, and down the street to where we were staying, introducing me to the owner I had emailed weeks before. It was an astounding display of generosity that is at the heart of why Japanese hospitality is unmatched.

Tokyo is amazing for being so meticulously run that you can house the largest metropolis on Earth and still contribute positively to the fact that it is in a country that is one of the safest on the planet, all the while being amazingly well kept with a distinct lack of the general grime that accumulates in the nooks and crannies of housing a population that large. When I went back to Japan in 2013, on the same trip Wendy and I visited Nara, we had earlier visited Tokyo, being graciously hosted part of the time by her cousin Vivien. On an outing that caught us in the morning train rush, when our stop arrived a young girl that had been by the door ahead of us stepped off the train, turned around, and began yelling at the man who had been behind her. Us learning in retrospect by way of Vivien's translation that she said the man was a pervert, that he was touching her, and that he should be ashamed. The accused gets off of the train but is grabbed by an older gentleman while an older woman asks the girl if she's sure that he's the one who did it because she's going to cause a lot of trouble for this man and that she needs to be really sure it was him. I was conflicted as we left, feeling a voyeuristic pleasure from having seen something I had only heard about before while being confused at the older woman's dismissal of the young girl's claims.

We had to rush to leave without seeing the resolution because we were already running late for a guided tour, having taken the wrong train to the wrong stop and trying to make our way back when we came across the morning commute incident. Vivien introduced us to the tour guide, explained that unfortunately she couldn't make it and that we don't speak Japanese but that Wendy and I would just follow the group. The guide seemed friendly, smiling a lot and being patient. The bus took us to Shosenkyo Valley, a beautiful nook of autumn color and water in the nearby mountains. After the valley and a meal and the tour of a vineyard we were headed to our final destination: a traditional Japanese public onsen. I was less nervous than I expected, stripping naked and joining almost two dozen other men, mostly middle-aged and older, in a set of hot springs nestled into the side of the mountain overlooking the valley. The view was fantastic even with the setting sun behind clouds, the air just chilly enough to make the warm water pleasent, a relaxing end to a day of wandering. Wendy sits with the women on the other side of a tall bamboo fence, enjoying the heat and the landscape but trying to hide her tattoo for fear of breaking house rules. I sit and listen to the older men talk and laugh until I think it's probably time to leave and find Wendy waiting for me outside at a group of benches. We sit, taking in the coming night, sharing a deep fried hard boiled egg snack before it's time to get on the bus and go home. The guide, who has been talking on and off with the rest of the group all day, finishes his set of speeches. He seems well received, the bus occasionally laughing, and I wonder what he's saying. In the end I just nod off as the sky turns dark.

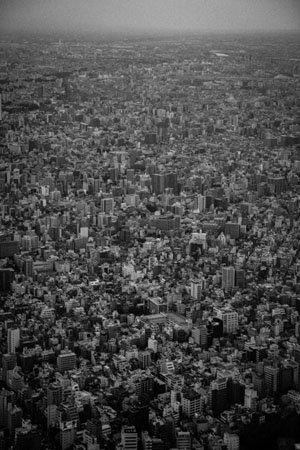

The next morning we were on our way to the Tokyo Skytree, the largest tower in the world with an observation deck at 450 meters (nearly 1,500 feet). It dwarfs the surrounding landscape, making ten story buildings look like houses and nearby downtown Tokyo skyscrapers look like inflated apartments. Almost as if flying over the metropolis, below me were thousands of buildings, millions of lives, each no doubt uniquely individual and yet now, from a distance, blurring into a seamless swath of mostly greys that dominate in all directions to the horizon. It was breathtaking, it was a marvelous testament to human achievement, but it also instantly reminded me of The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya wherein the main character is at a baseball game and suddenly realizes she is a dot among thousands in a full stadium and how many other countries full of people there are and how little she is in the midsts of all that. The realization causes her to manifest a new world to live in where aliens and magic and time travel are real, where she has control over what happens, where the world does revolve around her.

I had notions of what I wanted from Japan when I went. Less so in 2006 when I went with friends or in 2013 when I went with Wendy, but earlier that year, in 2013, when I left to go teach English in Japan. I was awarded a contract from an eikaiwa, of which there are many, that offer private English lessons to anyone, but mostly students and salarymen. I had assumed that the job would provide a steady structure that would break me of some of my lethargy and bad habits, the routines of my life that I saw as unhelpful towards my real goal: writing a novel and getting published. I saw it as a boot camp of sorts, to get me in shape for finally completing a manuscript, having three incomplete attempts under my belt. Being in Japan offered its own allure, but I knew better than to consider it a vacation. I knew that work was going to take up most of my time. The idea was to write around work, to have that take most of my free time and to enjoy Japan on the bursts of festivals and holidays throughout the year. Unfortunately the reality of a forty hour work week coupled with previously untold, unpaid overtime requirements and maintaining an apartment alone quickly burst my idyllic daydream of free time, much less the energy to use it to write. During one of our lessons I was talking with a student about daily routines and asked him to describe his day to me. He was a salaryman working in IT and said his company had a project in Tokyo. This means he woke up every morning at six, to leave by seven, to catch a two hour train into the city, to work from nine in the morning until nine at night because the special project requires consistent overtime, to get home at eleven to try and be in bed by midnight. I laughed and told him that I thought I was working hard before but that his schedule made me feel like I was being lazy. I asked him how long he had been doing this. He said the project is scheduled to take about a year and that he was about six months in. He said he'll be glad when it's over.

I did manage to start writing, the final week I was there, during one of the three national holiday weeks. I wrote slightly over four thousand words and realized I was going to have an incredibly difficult time trying to finish an my project anywhere at any time, much less while working those hours and cooking and cleaning and sleeping and drinking perhaps more heavily than is helpful. I messaged my staff, apologized for leaving on short notice, and headed to the airport slightly one month after arriving.

Wendy had already scheduled her vacation time to come see me in Japan for three weeks in October so we went back, getting a chance to visit her cousin and explore the country. After Tokyo we took a train to Kyoto, the old capital of Japan, an area known for its traditional Japanese architecture, countless temples, and lush countryside. It was a welcome slower pace, less crowded, greener, generally more relaxed. We had the chance to visit what became one of my favorite places in Japan: Fushimi Inari, a sprawling temple complex with thousands of torii gates set over paths leading up the mountain. The bright orange gates have kanji on one side and I ask Wendy to try and translate them. Because kanji characters are all borrowed from Chinese characters and Wendy can read Chinese, while she can't pronounce them in Japanese, many words carried their meaning over and she can decipher pieces from context. She says that each torii gate names who donated the funds to have it put up and when. In the beginning, when we first pass through the gates, all of the names are from Emperors, but as we ascend local business names begin to appear. It feels telling to me somehow, about how the burden of cultural cost has shifted, about how now a shop that's done well for itself has its name on the same path as those the country once considered gods. The higher we get, the more empty stumps of previous gates we see, the more rot on existing wood, the more signs showing what level of donation gets you what size of torii gate. Piles of smaller but still brightly colored wooden gates sit in piles at the numerous shrines that follow the path up the mountain. We make it to the top and almost miss it, the neverending stairs having us hypnotized in a climb, but as they begin to descend we stop and notice a shrine and a small shop, like so many others, innocuous, with a faded paper sign marking it as the top. Trees still dominate and block any sort of view but we stop and catch our breath and admire the shrine. We make our way down slower, the atmosphere enchanting, every turn of the path another picturesque, moss covered temple or cluster of gates. A young man with camera in hand sprints up the stairs and asks in English how far to the top and I tell him about ten minutes. He says thanks and keeps running. We meet him again just before we reach the bottom, still running. He asks where the train station is. I point and wonder how he got here.

The next day we were headed to Nara to meet our new AirBnB hosts, a middle-aged couple that rents out their bedrooms to travelers. Bob is an English teacher at a university in Osaka, having first come to Japan more than twenty years ago, initially working for the exact company I had quit from earlier that year. Lilly is Chinese born but with immaculate Japanese and English. Both have a love for the country but neither seem particularly surprised to hear about our encounter with the xenophobe. Bob mentions something that I've heard from others who have been in Japan for a long time: that there is no assimilation, that you will always be considered a foreigner, no matter how long you've been there or what color your passport is. It doesn't help that we're in the South, Bob explains, saying that Japan somewhat resembles America's geographic political divide. It's the older generation too, of course, that holds most strongly to the way things were, the younger generation more eagerly wearing European clothes and eating American foods.

Japan, along with the rest of the world, is wrestling with globalization, with trying to move towards a shared future while still holding on to its identity. Kyoto and Osaka, less than an hour apart by train, are a perfect example of this. Kyoto has become the symbol for Japan's past: the old capital with traditional architecture and culture. We ate one night at a soba restaurant that has been open since before Christopher Columbus had the idea to reach Asia by sailing west. We walked through the park at one of the Emperor's old palaces and saw grandmas in kimonos going for a stroll. Kyoto thrives, as a tourist destination and as a symbol, because of this. Osaka in turn is a modern phenomenon, an enormous metropolis, with millions of people and endless highrises. But as we take off from Osaka International Airport and I look down, the pale concrete, glittering windows, and spanning bridges could belong to any major city in the world. From far enough back to blur faces and words, technology has begun to homogenize us. Cookie cutter houses and neighborhoods become cookie cutter cities and metros. Cookie cutter media produces a generation of cookie cutter children. Our global community has begun to interbreed, to shave off the edges, to take to heart the notion that we are all equal. In a way this is of course beautiful. As a species with a long history of seeing fellow humans as less than human, the revelation that we aren't so different has been a long time coming. But I don't think the old man in Nara thought of me as subhuman. I very much doubt his goal is the extermination of the white race. I don't think he even cared that I was a foreigner in his country. I think what he and other conservatives like him fear is change and the loss of cultural identity. They have little faith that we can interact so much with others and continue to be ourselves. Every clothing store with an English name blaring American music while young men and women with bleached hair do their best to imitate California style sends waves of anxiety through a culture that has a fierce pride in its history and people. I became a flashpoint for the old man, proof once again that everything is falling apart, spinning out of control, and that someone needs to do something. It was men like this, I realized, that are part of why countries become unique. Similar men with similar feelings are why France and Germany are so geographically close and yet have dramatically different takes on language, art, food, and industry. These men were also the ones most firmly against the pull of another unifying technology, the Euro currency, because any submission of sovereignty is seen as a submission of cultural identity. It becomes easier to see why countries like Greece saw the rise of ultra-conservative political parties like Golden Dawn in response to the financial crisis of 2008.

It's easy for me, from my place of privilege, to empathize with a cantankerous old man that did little more than throw words at me. This isn't an attempt to whitewash the still ever present prejudices that so many people give and receive. Rather, it's a personal attempt to see the humanity in the worst of us, to not get discouraged with the pace of change I desperately want to see, to remember that even dark hearts feel they're doing good, and that opposing forces need each other to define who they are. Or, as the philosopher Alan Watts more succinctly put it, saints need sinners.

The two weeks I spent with Wendy in Japan were a dream vacation come true. So much of what I wanted to see and experience of Japan was revealed to me, from the scenic countryside to amazing food to cultural icons. I would love to visit again, to explore more bits and pieces of a land that's inspired me since my childhood; I still have notions of climbing Mt. Fuji to see the sun rise on the land of the rising sun. So even though I didn't stay, Japan continues to capture my imagination and influence my life from an ocean away.

Bob and Lilly continue invest in their home and business, opening more spaces to invite more people to come and share a country that's always been hesitant towards outsiders. A teacher colleague of mine, one that decided to stay, recently married a Japanese woman and announced they're having a child. Or, as Alan Watts more succinctly put it, the only way to make sense out of change is to plunge into it, move with it, and join the dance.

Almost all of my interactions in Japan were at least cordial and the majority were displays of vast humility and hospitality that I've never seen anywhere else I've traveled to. One particular old man, however, gave me a glimpse into a side of Japan that I had heard about but had never experienced. While looking for a place to eat with Wendy after a day of temple and deer viewing in Nara Park, I suddenly hear someone shout, in English, that I should go back where I came from. Confused at first I start laughing, unsure of the direction of the insult, but the old man quickly repeated himself and made it clear that he was talking to me. There was mention of my unwelcomeness, of my being unwelcome because I was taking their Asian women, that I should go home and get a woman from there. Expletives were introduced. His English was actually better than most people we had met. I mention that Wendy isn't Japanese but the man seems unfazed. We leave with mixed emotions and sit down to eat, still trying to process the encounter, when another old Japanese man sits down and immediately notices us. His face and voice give away his inebriated state, but he's all smiles and praises for American baseball and Hollywood movies, quoting his favorite films, telling me how much he likes the New York Yankees and Derek Jeter. His English isn't as good as the other old man, and he mixes in pieces of Italian and French, but his joviality couldn't be more clear. He laughs at all of his own jokes and offers me some sake, telling me the deer in Nara are protected and so I shouldn't shoot Bambi. He talks to us the entire time we're there until we go to leave, me thanking him for his generosity and the smile on his face having never left. The abrupt shift from one end of the spectrum to the other left me dazed, my head still spinning from two interactions that couldn't have been more different in the span of less than five minutes.

Japan has meant different things to me through my life. Growing up on video games and animated ninjas put a vision of a futuristic utopia based on an ancient noble heritage in my head, a notion that lasted long enough to take me there with two friends in 2006. In some ways the vision held up. Tokyo's train system is a marvel, expansive enough to get you anywhere in the city, accessible without knowing any Japanese. This is true for most of Japan, that you can travel the entire country by train, though English does tend to disappear outside of the major cities. I was also astounded by how polite almost every single person in the service industry was and how quick they were to go above and beyond to help an obviously clueless visitor.

In Yamanouchi, on our way to visit the Jigokundani Monkey Park to see the Japanese Macaque bath in the hot springs, we exit the only local station and immediately notice the lack of English anywhere. Without knowing what else to do, I pick a street at random and begin walking, hoping to find someone to try and mime directions with. I walk into a hotel, fancier than the pictures told me to expect from my booking, and ask the the lady behind the counter if she knows the direction of the address in my hand. Instead of pointing a finger or drawing a map on a notepad she walks out from behind the counter, out of the hotel, and down the street to where we were staying, introducing me to the owner I had emailed weeks before. It was an astounding display of generosity that is at the heart of why Japanese hospitality is unmatched.

Tokyo is amazing for being so meticulously run that you can house the largest metropolis on Earth and still contribute positively to the fact that it is in a country that is one of the safest on the planet, all the while being amazingly well kept with a distinct lack of the general grime that accumulates in the nooks and crannies of housing a population that large. When I went back to Japan in 2013, on the same trip Wendy and I visited Nara, we had earlier visited Tokyo, being graciously hosted part of the time by her cousin Vivien. On an outing that caught us in the morning train rush, when our stop arrived a young girl that had been by the door ahead of us stepped off the train, turned around, and began yelling at the man who had been behind her. Us learning in retrospect by way of Vivien's translation that she said the man was a pervert, that he was touching her, and that he should be ashamed. The accused gets off of the train but is grabbed by an older gentleman while an older woman asks the girl if she's sure that he's the one who did it because she's going to cause a lot of trouble for this man and that she needs to be really sure it was him. I was conflicted as we left, feeling a voyeuristic pleasure from having seen something I had only heard about before while being confused at the older woman's dismissal of the young girl's claims.

We had to rush to leave without seeing the resolution because we were already running late for a guided tour, having taken the wrong train to the wrong stop and trying to make our way back when we came across the morning commute incident. Vivien introduced us to the tour guide, explained that unfortunately she couldn't make it and that we don't speak Japanese but that Wendy and I would just follow the group. The guide seemed friendly, smiling a lot and being patient. The bus took us to Shosenkyo Valley, a beautiful nook of autumn color and water in the nearby mountains. After the valley and a meal and the tour of a vineyard we were headed to our final destination: a traditional Japanese public onsen. I was less nervous than I expected, stripping naked and joining almost two dozen other men, mostly middle-aged and older, in a set of hot springs nestled into the side of the mountain overlooking the valley. The view was fantastic even with the setting sun behind clouds, the air just chilly enough to make the warm water pleasent, a relaxing end to a day of wandering. Wendy sits with the women on the other side of a tall bamboo fence, enjoying the heat and the landscape but trying to hide her tattoo for fear of breaking house rules. I sit and listen to the older men talk and laugh until I think it's probably time to leave and find Wendy waiting for me outside at a group of benches. We sit, taking in the coming night, sharing a deep fried hard boiled egg snack before it's time to get on the bus and go home. The guide, who has been talking on and off with the rest of the group all day, finishes his set of speeches. He seems well received, the bus occasionally laughing, and I wonder what he's saying. In the end I just nod off as the sky turns dark.

The next morning we were on our way to the Tokyo Skytree, the largest tower in the world with an observation deck at 450 meters (nearly 1,500 feet). It dwarfs the surrounding landscape, making ten story buildings look like houses and nearby downtown Tokyo skyscrapers look like inflated apartments. Almost as if flying over the metropolis, below me were thousands of buildings, millions of lives, each no doubt uniquely individual and yet now, from a distance, blurring into a seamless swath of mostly greys that dominate in all directions to the horizon. It was breathtaking, it was a marvelous testament to human achievement, but it also instantly reminded me of The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya wherein the main character is at a baseball game and suddenly realizes she is a dot among thousands in a full stadium and how many other countries full of people there are and how little she is in the midsts of all that. The realization causes her to manifest a new world to live in where aliens and magic and time travel are real, where she has control over what happens, where the world does revolve around her.

I had notions of what I wanted from Japan when I went. Less so in 2006 when I went with friends or in 2013 when I went with Wendy, but earlier that year, in 2013, when I left to go teach English in Japan. I was awarded a contract from an eikaiwa, of which there are many, that offer private English lessons to anyone, but mostly students and salarymen. I had assumed that the job would provide a steady structure that would break me of some of my lethargy and bad habits, the routines of my life that I saw as unhelpful towards my real goal: writing a novel and getting published. I saw it as a boot camp of sorts, to get me in shape for finally completing a manuscript, having three incomplete attempts under my belt. Being in Japan offered its own allure, but I knew better than to consider it a vacation. I knew that work was going to take up most of my time. The idea was to write around work, to have that take most of my free time and to enjoy Japan on the bursts of festivals and holidays throughout the year. Unfortunately the reality of a forty hour work week coupled with previously untold, unpaid overtime requirements and maintaining an apartment alone quickly burst my idyllic daydream of free time, much less the energy to use it to write. During one of our lessons I was talking with a student about daily routines and asked him to describe his day to me. He was a salaryman working in IT and said his company had a project in Tokyo. This means he woke up every morning at six, to leave by seven, to catch a two hour train into the city, to work from nine in the morning until nine at night because the special project requires consistent overtime, to get home at eleven to try and be in bed by midnight. I laughed and told him that I thought I was working hard before but that his schedule made me feel like I was being lazy. I asked him how long he had been doing this. He said the project is scheduled to take about a year and that he was about six months in. He said he'll be glad when it's over.

I did manage to start writing, the final week I was there, during one of the three national holiday weeks. I wrote slightly over four thousand words and realized I was going to have an incredibly difficult time trying to finish an my project anywhere at any time, much less while working those hours and cooking and cleaning and sleeping and drinking perhaps more heavily than is helpful. I messaged my staff, apologized for leaving on short notice, and headed to the airport slightly one month after arriving.

Wendy had already scheduled her vacation time to come see me in Japan for three weeks in October so we went back, getting a chance to visit her cousin and explore the country. After Tokyo we took a train to Kyoto, the old capital of Japan, an area known for its traditional Japanese architecture, countless temples, and lush countryside. It was a welcome slower pace, less crowded, greener, generally more relaxed. We had the chance to visit what became one of my favorite places in Japan: Fushimi Inari, a sprawling temple complex with thousands of torii gates set over paths leading up the mountain. The bright orange gates have kanji on one side and I ask Wendy to try and translate them. Because kanji characters are all borrowed from Chinese characters and Wendy can read Chinese, while she can't pronounce them in Japanese, many words carried their meaning over and she can decipher pieces from context. She says that each torii gate names who donated the funds to have it put up and when. In the beginning, when we first pass through the gates, all of the names are from Emperors, but as we ascend local business names begin to appear. It feels telling to me somehow, about how the burden of cultural cost has shifted, about how now a shop that's done well for itself has its name on the same path as those the country once considered gods. The higher we get, the more empty stumps of previous gates we see, the more rot on existing wood, the more signs showing what level of donation gets you what size of torii gate. Piles of smaller but still brightly colored wooden gates sit in piles at the numerous shrines that follow the path up the mountain. We make it to the top and almost miss it, the neverending stairs having us hypnotized in a climb, but as they begin to descend we stop and notice a shrine and a small shop, like so many others, innocuous, with a faded paper sign marking it as the top. Trees still dominate and block any sort of view but we stop and catch our breath and admire the shrine. We make our way down slower, the atmosphere enchanting, every turn of the path another picturesque, moss covered temple or cluster of gates. A young man with camera in hand sprints up the stairs and asks in English how far to the top and I tell him about ten minutes. He says thanks and keeps running. We meet him again just before we reach the bottom, still running. He asks where the train station is. I point and wonder how he got here.

The next day we were headed to Nara to meet our new AirBnB hosts, a middle-aged couple that rents out their bedrooms to travelers. Bob is an English teacher at a university in Osaka, having first come to Japan more than twenty years ago, initially working for the exact company I had quit from earlier that year. Lilly is Chinese born but with immaculate Japanese and English. Both have a love for the country but neither seem particularly surprised to hear about our encounter with the xenophobe. Bob mentions something that I've heard from others who have been in Japan for a long time: that there is no assimilation, that you will always be considered a foreigner, no matter how long you've been there or what color your passport is. It doesn't help that we're in the South, Bob explains, saying that Japan somewhat resembles America's geographic political divide. It's the older generation too, of course, that holds most strongly to the way things were, the younger generation more eagerly wearing European clothes and eating American foods.

Japan, along with the rest of the world, is wrestling with globalization, with trying to move towards a shared future while still holding on to its identity. Kyoto and Osaka, less than an hour apart by train, are a perfect example of this. Kyoto has become the symbol for Japan's past: the old capital with traditional architecture and culture. We ate one night at a soba restaurant that has been open since before Christopher Columbus had the idea to reach Asia by sailing west. We walked through the park at one of the Emperor's old palaces and saw grandmas in kimonos going for a stroll. Kyoto thrives, as a tourist destination and as a symbol, because of this. Osaka in turn is a modern phenomenon, an enormous metropolis, with millions of people and endless highrises. But as we take off from Osaka International Airport and I look down, the pale concrete, glittering windows, and spanning bridges could belong to any major city in the world. From far enough back to blur faces and words, technology has begun to homogenize us. Cookie cutter houses and neighborhoods become cookie cutter cities and metros. Cookie cutter media produces a generation of cookie cutter children. Our global community has begun to interbreed, to shave off the edges, to take to heart the notion that we are all equal. In a way this is of course beautiful. As a species with a long history of seeing fellow humans as less than human, the revelation that we aren't so different has been a long time coming. But I don't think the old man in Nara thought of me as subhuman. I very much doubt his goal is the extermination of the white race. I don't think he even cared that I was a foreigner in his country. I think what he and other conservatives like him fear is change and the loss of cultural identity. They have little faith that we can interact so much with others and continue to be ourselves. Every clothing store with an English name blaring American music while young men and women with bleached hair do their best to imitate California style sends waves of anxiety through a culture that has a fierce pride in its history and people. I became a flashpoint for the old man, proof once again that everything is falling apart, spinning out of control, and that someone needs to do something. It was men like this, I realized, that are part of why countries become unique. Similar men with similar feelings are why France and Germany are so geographically close and yet have dramatically different takes on language, art, food, and industry. These men were also the ones most firmly against the pull of another unifying technology, the Euro currency, because any submission of sovereignty is seen as a submission of cultural identity. It becomes easier to see why countries like Greece saw the rise of ultra-conservative political parties like Golden Dawn in response to the financial crisis of 2008.

It's easy for me, from my place of privilege, to empathize with a cantankerous old man that did little more than throw words at me. This isn't an attempt to whitewash the still ever present prejudices that so many people give and receive. Rather, it's a personal attempt to see the humanity in the worst of us, to not get discouraged with the pace of change I desperately want to see, to remember that even dark hearts feel they're doing good, and that opposing forces need each other to define who they are. Or, as the philosopher Alan Watts more succinctly put it, saints need sinners.

The two weeks I spent with Wendy in Japan were a dream vacation come true. So much of what I wanted to see and experience of Japan was revealed to me, from the scenic countryside to amazing food to cultural icons. I would love to visit again, to explore more bits and pieces of a land that's inspired me since my childhood; I still have notions of climbing Mt. Fuji to see the sun rise on the land of the rising sun. So even though I didn't stay, Japan continues to capture my imagination and influence my life from an ocean away.

Bob and Lilly continue invest in their home and business, opening more spaces to invite more people to come and share a country that's always been hesitant towards outsiders. A teacher colleague of mine, one that decided to stay, recently married a Japanese woman and announced they're having a child. Or, as Alan Watts more succinctly put it, the only way to make sense out of change is to plunge into it, move with it, and join the dance.